By Howard W. French

Howard French, a leading American journalist on Africa for four decades, returned to the continent after stints as New York Times correspondent in Tokyo and Shanghai. He discovered a resurgent continent increasingly wedded to Chinese growth and expansion. The deep penetration of Africa by Chinese firms and citizens has coincided with an era of sustained African economic growth. On the eve of President Obama’s visit to three democratic nations – Senegal, South Africa, and Tanzania – French’s essay initiates an Africa Demos series on the China-Africa Convergence and their implications for the United States and other countries.

For the last three years, I have traveled extensively in sub-Saharan Africa, after an unaccustomed absence. My recent experiences, which have ranged through every region of the subcontinent, tell me two essential things: Africa is caught up in intense and rapid change, and American policy toward the continent is not adjusting fast enough.

A trickle of articles in the American press has belatedly recognized Africa’s strong run of economic growth. Some of them have touted the expansion of a new African middle- or consumer-class, which by some measures is larger than that of India. Others have focused on the continent’s overall economic growth, drawing on data and forecasts from the International Monetary Fund and other sources. These suggest that over the next several years, Africa will grow faster than any other continent, including Asia.

The Demographic Transformation

The bullish economic data do not fully capture the feeling on the ground. In places like Lagos, Accra, Lusaka, Dar es Salaam and Maputo, a vast region of the world is on the move. To comprehend the scale of the changes underway, and the special nature of this moment, it must be seen that demographic trends are as important as GDP statistics. Two insufficiently appreciated facts stand out.

Africa’s population is growing faster now than ever in history, and this growth is accelerating. This development can be understood as a belated recovery from the depredations of the centuries-long slave trades. Together with the prevalence of tropical diseases, especially in the long era before the introduction of modern medicine, the continent’s human development was sharply suppressed. Africa’s current population momentum is so great, though, that by mid-century it is expected to double in size, reaching two billion according to U.N. estimates.

Two other trends of surpassing importance flow from the strong population growth. Africa has entered what experts call a demographic “sweet spot.” For the next few decades, the distribution of people by age will be sharply skewed toward the young, who are energetic, eager to work and maximally productive. The countries that are making the smartest investments in education will put themselves in a good position to compete in the vitally important global manufacturing and service sectors, especially as labor costs in China, whose population is rapidly aging, rise.

Scenarios of Extraordinary Opportunity

Sub-Saharan Africa overall is already investing heavily in education, surpassing many other parts of the world in terms of the percentage of national spending devoted to school and job training. But even against this positive backdrop, the continent needs to do much more, and so does the United States, which is ideally suited to help in this area. With almost no fanfare, this country has played a huge role in improving African health, most notably through the Pepfar program, which has made extraordinary inroads against HIV in many countries.

It is time to turn American energies toward similar big impact goals in education, including drastically reducing illiteracy, which especially affects girls and persists at intolerable levels in regions like the Sahel. Another challenge ideally tailored to America’s strengths would be helping dramatically reinvigorate African universities and integrate them more closely into the global knowledge grid.

The final piece of the demographic puzzle relates to the explosive growth of Africa’s cities. The continent is urbanizing at rates unsurpassed in human history. The number of cities is exploding, and with it the number of mega-cities. This creates scenarios of extraordinary opportunity for countries that are forward thinking and dynamic.

Cities are arguably humankind’s greatest invention; they dramatically accelerate the velocity of economic exchange and the communication of ideas, and they can hugely expand opportunity for their residents, along with economic productivity. The creation of new cities on the present scale in Africa offers a chance that populations in older countries can only dream of: to innovate in urban design and create maximally efficient, human-friendly living and working environments. The United States has a big potential role to play in helping African nations think through issues of urban creation, renewal and planning, as well as the development of better systems of sanitation, power, transportation and housing. These need not be driven solely by aid. Rather, the United States and American companies should step up to this challenge as investors and builders.

Chinese vs. American Perceptions of Africa

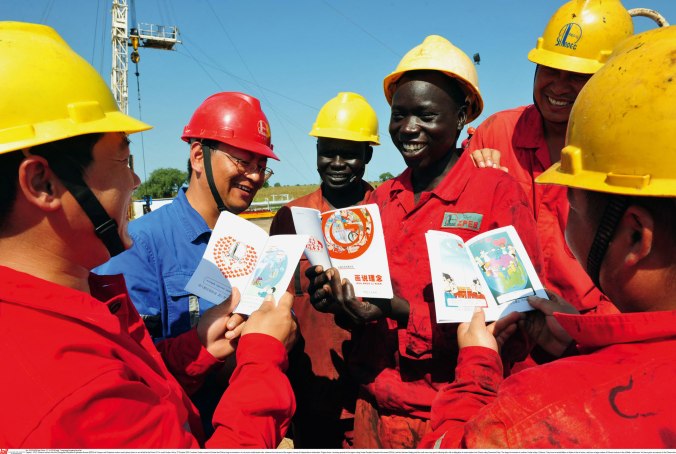

Perceiving opportunities like these and many others, however, will first require a revolution in American thinking about Africa. I have spent the last few years working on a book about China’s relationship with the continent, and could not have been more struck by the differences in attitude in the United States and China toward Africa. More than a million Chinese have moved to Africa in the last decade, largely because they see the continent as an arena of almost limitless opportunity. This holds true from big company executives to mom and pop entrepreneurs from China’s inland, second tier cities.

Americans, meanwhile, despite their far deeper historical associations with the continent, including 13 percent of the population that traces its ancestry to Africa, cling to deeply engrained attitudes toward this part of the world, as a place of war, of misery, of strife, etc. For this reason, and because we cannot get over a long-running sense of Africa as a place to be aided, we are ill equipped to see or appreciate the opportunities that Africa offers.

The American press perpetuates old patterns of coverage even as Africa rapidly grows and changes. The work of Jeffrey Gettleman of the New York Times, a recent winner of the Pulitzer Prize, is the most prominent and arguably influential example of this tendency. In a 2012 essay in the New York Review of Books that broadly reflects the focus of his work as East Africa bureau chief for the Times, he wrote: “What we are seeing is the decline of the classic wars by freedom fighters and the proliferation of something else—something wilder, messier, more predatory, and harder to define… Today the continent is plagued by countless nasty little wars, which in many ways aren’t really wars at all. There are no front lines, no battlefields, no clear conflict zones, and no distinctions between combatants and civilians.”

What the facts tell us about Africa is quite the contrary. As Jonathan Berman wrote in a recent Harvard Business Review blog post, titled “Africa is more stable than you’ve been led to think,” which drew its data from the Economist: “Across Africa, successful coups are rare and getting rarer. This Economist Intelligence Unit has tracked the trend since 1960, shortly after colonial withdrawal began. Given the preconceived impression of Africa as coup crazy, many lose sight of the decline of coups… Africa’s governments aren’t just becoming more stable. They’re becoming more representative, albeit in an irregular pattern, as befits a continent with 54 countries. The Polity IV Project measures political regimes on a spectrum from fully institutionalized autocracies (low scores) to fully institutionalized democracies (high scores)… The trend since 1990, across all of Africa, has been towards more democracy.”

No one expects the press to abandon conflict as a topic, but the American media are long overdue for a re-set in terms of the ways they habitually frame African coverage. This should start with a repudiation of the way that African events are denied specificity. Things are routinely said to take place “in Africa,” or “across Africa” instead of in actual countries or places with real names. The eternal pretext is to “make it easier” for the reader, who can’t be bothered with too many unfamiliar names. This kind of factual looseness, though, is not practiced toward any other part of the world, and bespeaks a casual and persistent ghettoization of Africa.

Another example of this is the fact that virtually no American news organization offers business coverage of Africa. Return on investment in Africa is among the highest in the world. Trade with each region of the continent is booming. And recently, big U.S. companies like Walmart, IBM and Google, to name the most prominent examples, have been expanding their presence in Africa. But because the media speaks mainly in terms of conflict and aid, the general public has no perception of the growing opportunities on the continent, unlike the large numbers of Chinese newcomers.

Will Obama Energize U.S.-Africa Engagement?

This, finally, points the way to what is needed from America’s political leaders during the remainder of the Obama Administration and beyond. Putting an end to the ghettoization of Africa will require concerted effort at the top. Senior officials must, as Chinese leaders have been doing for years, visit the continent frequently. We must also put an end to the belittling, small ball ritual whereby African leaders are invited to Washington in groups of three or four (as if an African country by definition didn’t merit a one-on-one discussion), offered a quick photo opportunity, a few homilies about democracy and governance and then sent on their way.

The administration needs to be much more energetic and resourceful in encouraging American businesses to seek out opportunities in Africa. The profit motive is the best cure for the deep-seated strain of paternalism that runs through our relations with the continent. During my book research travels, I was surprised to learn in country after country that construction projects, worth as much as $200 million that are American financed through the Millennium Development Corporation, drew no bids from American companies. China was gobbling up this work until Congress passed a law saying that funding from the MDC could not be given to state owned companies.

In one capital city after another, I noticed that American embassies had shuttered their “commercial sections,” which historically have researched African economies and provided helpful information and contacts to American businesses looking for opportunities. In most of those cities, the Chinese have recently opened shop with their own commercial offices, usually not tucked away in an embassy, but housed in a well-appointed building of its own.

To avoid misunderstanding, it must be emphasized that Washington’s biggest problem with Chinese inroads in Africa has nothing to do with China. The real problem is that the United States has walked away from Africa, leaving the playing floor virtually empty, and it will take years of concerted political leadership, and not gimmicky laws, to get back in the game.

Finally, it must be said bluntly that President Obama’s mere two visits in five years have been a big disappointment. It is a tremendously positive thing that his second visit to the continent consists solely of democracies. For decades, Washington’s closest ties on the continent have been with a series of authoritarian states. This administration’s generally low profile in Africa, however, has squandered the immense opportunity that the election of a politician of African heritage had for resetting and reinvigorating America’s relationships on the continent. Yes, we live in a big and busy world, but the changing dynamics of Africa deserve much more of our attention, and offer prospects of outsized rewards for both America and for Africa.

Howard W. French is an associate professor at the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University. He is the author of “A Continent for the Taking: The Tragedy and Hope of Africa,” and of the forthcoming “China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa,” to be published by Knopf in May 2014.

Africa Demos Forum is inspired by the Africa Demos quarterly published by Emory University and the Carter Center, 1990-1995: http://books.northwestern.edu/viewer.html?id=inu:inu-mntb-0006443104-bk

Copyright © 2013 AfricaPlus