By: Richard Joseph

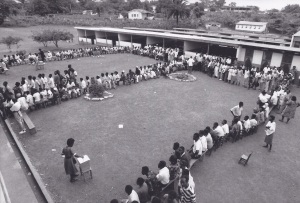

Ghana General Elections, December 1992

Photo Credit: Anthony Allison

In a March 29, 2013 meeting with four African presidents, President Barack Obama praised the democratic and economic progress in the continent. “How do we continue to build,” he asked, “on strong democracies?” “How do we continue to build on transparency and accountability?” His answer was forthright: “When you’ve got good governance — when you have democracies that work, sound management of public funds, transparency and accountability to the citizens that put leaders in place — it is not only good for the state and the functioning of government, it is also good for economic development.”

These fine words echo what Mr. Obama has said on earlier occasions, and notably his historic Address to Ghana’s Parliament in July 2009. Despite the achievements, however, full constitutional democracy has not yet become the predominant system in sub-Saharan Africa. Democratic advances are countered by retreats, precipitously in the cases of Mali and the Central African Republic. Kenya is balanced on a 50.07 vote for Uhuru Kenyatta as president, recalling the slender victory of John Atta Mills in Ghana’s 2007 presidential election. Yet Ghana weathered the challenge and continues to advance politically, economically, and in other ways. The most populous African country, however, Nigeria, has not consolidated its electoral democracy, 14 years after the last military regime departed. And Zimbabwe, so materially endowed, has yet to break decisively with authoritarianism, now accomplished by its neighbors, Malawi and Zambia.

At this juncture, it is appropriate to retrace the difficult journeys travelled since the democratic awakening in sub-Saharan Africa two decades ago. In the summer of 1990, as autocratic and military governments yielded to mounting demands for political change, a group of students and faculty of Emory University, Atlanta, convened to create a Comparative Research Project on African Democracy (see appendix). They recognized the urgent need to monitor and analyze these processes. Just a few months later, their discussions led to the publication of a quarterly bulletin, Africa Demos, by the African Governance Program of the Carter Center. Today, anyone worldwide can read the digitized issues, 1990-1995, thanks to the collaboration of the Carter Center and Northwestern University Library: http://books.northwestern.edu/viewer.html?id=inu:inu-mntb-0006443104-bk.

The Arab Spring has become mired in conflict and confusion. What was the experience in sub-Saharan Africa over the past quarter-century? How did so many countries emerge from the turmoil with substantially democratic systems? How did political liberalization, and other governance reforms, facilitate the economic renaissance? These and other important questions will be taken up in the Africa Demos Forum hosted on AfricaPlus. Since the bulletin covered continental Africa, it can contribute to the comparative study of democratization in north and sub-Saharan Africa, as well as globally.

The Africa Demos Forum resumes what was a regular component of the original publication. Scholars and analysts, as before, will be invited to publish essays on key topics or on specific country experiences. Brief responses to their arguments will be posted from other participants. In this way, we hope to generate an informed, constructive, and interactive debate on major issues in democracy-building. The first issue of the bulletin, after restating the origins of democracy in the Greek word, demos – the greater number of citizens and their assembly to conduct public affairs – affirmed that democracy’s meaning is constant: “the people should govern themselves, and those who act in their name should be regularly accountable to the governed.” Two decades later, political freedom has not only been renewed in sub-Saharan Africa, it has survived many challenges, including periodic attempts to have it mean something other than government of, by, and for the people.

Africa Demos contains such a wealth of information and insights that I will limit myself to reflecting on its first year of publication, November 1990 – November 1991. Since the entire set can be printed, a 210-page ebook has, in effect, been made available to all for study, research, and instruction. We began by distinguishing African political systems as strong, moderate, ambiguous, or contested sovereignty, and soon moved to identifying four categories of systems and four degrees of commitments to democracy. Although this framework persisted, we recognized the need for a more advanced methodology called the Quality of Democracy Index. However, the challenge of implementing it exceeded our capacity.

The “fragile nationhood” of many African countries showed the need for “political engineering”. “Creative remodeling of the state to promote decentralization,” we argued, “must be courageously pursued in ways that do not undermine national sovereignty”. The insightful views of Richard L. Sklar were a constant source of inspiration. They include his claims that Africa was “a workshop of democracy”; his conception of democracy as inherently “an experimental process”; and his conviction that Africa had much to teach the world, especially about governmental authority deriving from indigenous systems as well as reflecting external models.

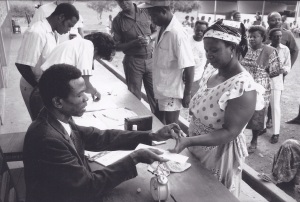

Zambian General Elections, October 1991

Observing Ballot Counting: President and Mrs. Carter, Richard Joseph, J. Brian Atwood and Eric Bjornlund (NDI)

Some of the commentaries read as if they were written today: on how geopolitics can override democracy promotion; the importance of ensuring that the fruits of an economic upturn are fairly shared among all social strata; on the need to connect democracy to peace-building among Africa’s diverse peoples; and the importance of ending the double standard of vigorous support for democratic reforms in some countries while coddling dictators in others. We published criticisms that came our way. Some were insightful and constructive; others reflected the very challenges to be confronted.

The Ambassador of Djibouti “vehemently’ objected to the designation of his country as “‘authoritarian’ simply because it hasn’t yet adopted the ‘quantitative’ aspect of reform…” The Moroccan Ambassador disputed that his government had shown a “weak or ambiguous commitment to democratization“. It should, he argued, have been “included in the essentially democratic countries”. In the same issue, the country report on Morocco concluded: “past reforms have produced limited and ineffectual democracy… Little is likely to change until [King] Hassan begins to share, if not relinquish, real political power.”

Africa Demos also served as a megaphone for African scholars and political activists. In just its first year, the views of Neville Alexander, Adu Boahen, Achille Mbembe, Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, Dele Olojede, Zene Tadesse, and Johan Van der Vyver were featured. Highlighted quotes were a notable feature. Sometimes they reinforced arguments made in the commentaries, such as Claude Ake’s contention that social pluralism is an argument for a democratic form of government as it enables differences to be negotiated, conciliated, and “moved to a higher order of synthesis.” In another vein, the words of Africa’s autocrats espousing democracy, such as Daniel arap Moi or Omar Bongo, spoke for themselves. In retrospect, certain quotations are particularly poignant, such as the declaration of Isaias Afewerki in 1990 that “the EPLF… has never entertained the illusion of monopolizing power in Eritrea”.

The democratic upsurge in Africa was accompanied by continuing warfare in several countries: Angola, Ethiopia, Liberia, Mozambique, and Sudan. Special attention was devoted to the independence of Namibia in March 1990, a month after a seminar of the African Governance Program. Ending Africa’s major wars was as important as promoting peaceful competitions for political power through fair elections. At the Carter Center, the pursuit of democratic progress has therefore been promoted alongside peace-building, eradicating infectious diseases, introducing improved agricultural methods, and bolstering human rights.

A new generation of democracy scholars has emerged since the events covered in the bulletin. The Africa Demos Forum will make it possible for established scholars, some of whom appeared on the pages of Africa Demos – such as Michael Bratton, Deborah Brautigam, Nelson Kasfir, Patrick Molutsi, Nicolas van de Walle, and Crawford Young – to contribute alongside rising scholars. A few, such as the courageous Masipula Sithole of Zimbabwe, are sadly no longer with us. Some student members of the editorial staff, such as Amy Poteete and Scott Taylor, have become astute Africanist scholars. In 1997, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, a generous funder of Africa Demos alongside other foundations, supported the publication of evaluative essays of the publication by ten African scholars. We will make that booklet available anew, and explore other ways to fulfill our abiding commitment to democratic empowerment through the production and dissemination of knowledge.

Appendix

Comparative Research Project on African Democracy

The Carter Center of Emory University (Summer 1990)

The winds of political change have reached Africa, blowing southwards from the democratic revolutions in Eastern Europe and northwards from the liberation struggles in southern Africa. When Nelson Mandela emerged from the South African prison system after 27 years, he pushed open a door for all political detainees and dissidents in Africa.

In February 1989, the African Governance Program of the Carter Center and Emory University conducted a path-breaking seminar that result in two seminal publications which identified the fundamental resources and avenues for political reform in Africa: Perestroika without Glasnost in Africa and Beyond Autocracy in Africa. A similar series of publications based on a March 1990 meeting on “African Governance in the 1990s: What can be done?” is currently in preparation.

The list of African governments that have indicated a willingness to liberalize their political systems grows almost weekly. It includes Angola, Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Guinea and Mozambique. Some other governments are resolute in resisting pressures for change, such as those of Cameroon and Kenya, while a few others, such as Robert Mugabe’s in Zimbabwe, seem determined to take their country in a more authoritarian direction.

To meet the demands posed by these developments, the African Governance Program has created a Comparative Research Project on African Democracy. It is conducted by a team of Emory University faculty and graduate students, initially from the Political Science Department, and assisted by student interns from Emory and other U.S. universities. Its work is directed by Dr. Richard Joseph, Carter Center Fellow, in association with Dr. Courtney Brown and Mr. William Downs, recipients respectively of a summer faculty fellowship and research assistantship funded by a grant to the Carter Center from the Hewlett Foundation.

The research team has set itself the following initial tasks:

- to collate in a systematic way relevant information about political transitions in Africa

-

to create computer-based models of the different processes of transition

-

to identify the major hurdles to political reform in African countries

-

to suggest ways in which these transitions can be assisted by external actors and agencies

To facilitate the work of this project, we welcome information and ideas that are pertinent to the above tasks. Occasional bulletins will be published making known our findings and suggestions. Individuals and/or organizations wishing to be placed on our mailing list should send us their names and addresses. This project will also produce materials for consultations that will be held at the Carter Center and Emory University. In collaboration with other research and policy institutes, we hope eventually to serve as a clearinghouse for information and advice about these vital but precarious transitions to constitutional democracy.